A personal health crisis is what Olympian Michael Frater said got him interested in the medicinal benefits of cannabis and eventually led to the opening of the 4/20 Therapeutic Bliss dispensary in Manor Park, Kingston on Saturday.

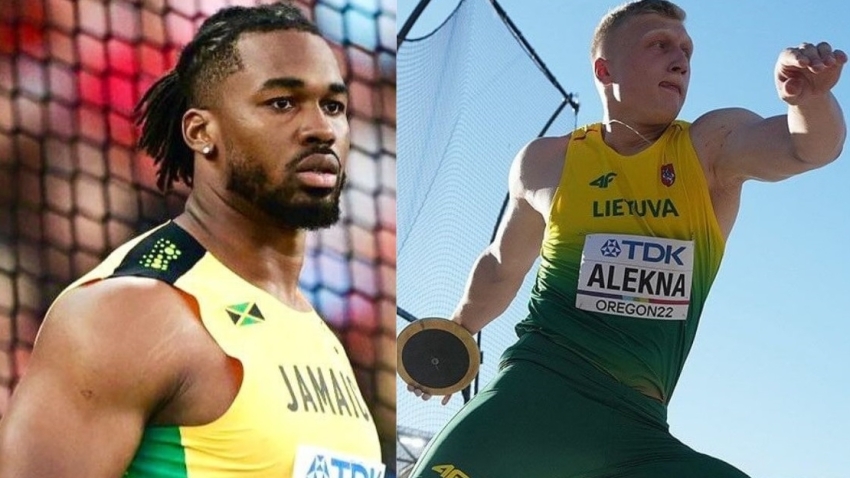

Frater, 38, represented Jamaica at the senior level for more than a decade, winning gold medals as a member of Jamaica’s world-record-setting 4x100m relay teams at the World Championships in Daegu, South Korea in 2011 and again at the London Olympics in 2012.

He also won a silver medal in the 100m at the 2005 World Championships in Helsinki, Finland. He was also a 100m champion at the 2003 Pan American Games in the Dominican Republic.

However, about five years ago persistent problems with his knees forced him to retire.

At Saturday’s launch, he explained how those knee problems introduced him to the healing properties of cannabis.

“I had very bad knees, and I remember waking up one day, and my knees were swollen, and I couldn’t walk. I went to the University Hospital (of the West Indies) where I met with Dr (Carl) Bruce and ran some tests but nobody could figure out what was wrong,” he told the gathering that included Jamaica’s Minister of Sports Olivia Grange, former world record holder Asafa Powell and Jamaica and West Indies cricketer Chris Gayle.

Christopher Samuda, President of the Jamaica Olympic Association and Ali McNab, an advisor to the sports minister were also in attendance and were in rapt attention as Frater shared his harrowing experience.

“I had an IAAF (World Athletics) function in Monaco. I remember leaving on Monday and got there on Tuesday and I couldn’t even walk off the plane. They had to send a wheelchair for me,” he recalled.

Initially, doctors in Monaco believed his condition was the result of doping, he said, but subsequent tests disproved their theories even though they were still unable to determine what was the cause of the constant swelling and fluid build-up in his knees.

He spent two weeks in hospital there where doctors ‘patched’ him up enough to enable him to fly home.

A subsequent visit to a medical facility in Florida was also unable to help him get any closer to identifying what was wrong with his knees, he said which left him fearing he would spend the rest of his life in a wheelchair.

It was then that his father, Lindel Frater, suggested he tried cannabis oil. He tried it and within a month he felt ‘brand new’, he said.

“I started studying a lot about it and realized that a drug that has been taboo for most of my life is really a miracle drug. It’s really a drug that once taken properly with the proper prescription, the medicinal purposes are exponential.”

Minister Grange applauded the retired Olympian and praised him for his initiative in opening the dispensary. She eventually made the first purchase of medicinal marijuana. Samuda also shared similar sentiments while praising Frater for his venture into the cannabis industry.

Gayle, meanwhile, said Frater’s venture was an example for other retired athletes to emulate.

“I am a big supporter of Michael's career and now his business venture, and from a sportsman's point of view, there is life after your original career and to actually venture in a business is good for him and we are here to support him 100 per cent,” said Gayle.

Powell, who was Frater’s teammate on several national teams, said, his friend and colleague, was always a budding entrepreneur.

“From ever since, Michael has always been the brains among all of us. He has always been driven, business-oriented. I have always admired that about him,” said the former 100m world record holder who brought his wife Alyshia along.

“It’s kind of intimidating sometimes when you’re talking to him, and he is saying some stuff I don’t even know about, so I have always known he would make this step into business.

“He keeps pushing and I am very, very happy for him.”